Last week, Microsoft announced some details of anti-piracy measures in Windows 7. It sounds like they’re going to be slightly less intrusive than those in Vista, and probably roughly as effective.

I don’t exactly resent all this product validation stuff. I’d prefer it if Microsoft didn’t feel the need to do it; but I accept that the company has a legitimate interest in dissuading casual copying, and to me a one-time online authorisation doesn’t seem an unreasonable way of going about that.

But I do resent all the weasel words and spin that surround the process.

A dubious history

I mean, let’s go back to the start. When online authorisation was introduced with Windows XP, Microsoft described it as “product activation” – a name that made it sound like a trivial necessity. Of course, that was (to put it kindly) a euphemism: how is a fresh installation of XP “inactive”?

Then in 2005 the company started talking about “genuine” Windows, and contrasting it with “counterfeit” software. Er, what? Is there a sweatshop in China somewhere where programmers are churning out knock-off DLLs and shonky service packs?

Of course not. The passing off of fake goods is a real problem in the Far East, but so far as I’m aware it’s not a major concern in the English-speaking territories at which this rhetoric is aimed. The focus on counterfeiting looks rather more like an attempt to discredit unlicensed software with a term that suggests it’s of inferior quality.

In reality, of course, the difference between “genuine” and “counterfeit” software is often nothing more than a 25-character code.

An advantage you can’t refuse

To promote its new notion of “genuine” software, the company also started touting the “Windows Genuine Advantage” – another heavily nuanced term. The “advantage” here was that if you allowed Microsoft to verify your Windows licence you wouldn’t be punished.

But if your installation wasn’t validated as “genuine”, your access to OS updates was restricted. And if Microsoft considered that your product key had been used too many times, it installed software on your machine that would nag you to buy a new licence.

And the best bit is that, after hobbling your Windows installation in this way, WGA then sympathetically explained that perhaps you had been “a victim of software counterfeiting”.

Of course, if you’re using Windows without a licence you have no right to expect a full Windows Update service. And arguably you’ve no right to complain when the developer modifies the code in unhelpful ways. Like I say, it’s not Microsoft’s anti-piracy measures I object to: it’s the slimy way they try to dress them up as somehow for our benefit that sticks in the throat.

Don’t believe what you read in the papers

WGA and “product activation” were developed further in Vista, and at the same time Microsoft stepped up its spin campaign, putting out three reports bewailing the dangers of unlicensed software.

The most credible was the first, a 2006 IDC report entitled The Risks of Obtaining and Using Pirated Software (PDF). This study found that “obtaining and using pirated software can pose a serious security risk.” That’s true, so far as it goes – though the danger identified by the researchers came from malware hosted on warez sites, not from the pirated software itself.

The other two reports were less persuasive. Last October’s Harrison Group report, Impact of Unlicensed Software on Mid-Market Companies (PDF), claimed to show that unlicensed software caused “poor business performance”; but as I noted at the time, its methodology was fundamentally flawed.

And then, in March, came Microsoft’s own anti-piracy paper, The Surprising Risks of Counterfeit in Business (PDF). Despite the title, there was nothing surprising in this paper: it effectively just parrotted the (questionable) findings of its predecessors.

But that’s all right: simply by keeping up a steady flow of such papers, the company is establishing a body of published research that seems to support the idea that unlicensed software is inherently dangerous and unreliable.

Moving with the times

In the meantime, the team that actually develops Windows has undergone a significant philosophical shift. The hubris of the Vista launch has given way to a fitting humility. Managers are acknowledging past mistakes, and making honest efforts to fix them. Windows 7’s improvements in responsiveness, usability and customisation suggest a new respect for the user.

And this change in tone is visible even in its anti-piracy technologies: “reduced functionality mode” isn’t coming back, and there’s no longer a forced delay in logging on to a system that’s out of its activation “grace period”.

In the glow of this optimistic new dawn, last week’s announcement was only the more aggravating.

For while Joe Williams, general manager for “Genuine Windows”, confirmed the new, less intrusive anti-piracy measures in Windows 7, he also made clear that the party line on piracy hasn’t evolved at all. Here again was “genuine high-quality Microsoft product”; here again was “malicious code” supposedly lurking within “counterfeit software.” Here, again, the constant empty reassurance that all this hoopla is really for our benefit.

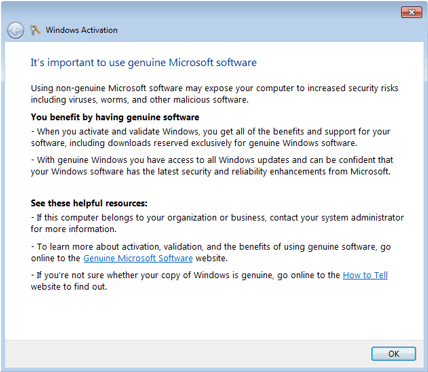

Within the software too, the high priests of WGA cling to their dogma. In Windows 7, if you don’t “activate” your OS within Microsoft’s stipulated timeframe, it brings up this warning:

Really, you have to wonder how many people are won over by all this slanted rhetoric and how many (like me) are insulted by it. Hell, I’d be far happier giving my money to Microsoft if it didn’t feel so much like caving in to manipulation.

It’s high time the “Genuine Windows” boys took a lesson from the Windows developers… and start playing straight with us.

If you enjoy getting angry at disingenuous rhetoric, may I also recommend Microsoft’s WGA Blog, penned by Microsoft product manager Alex Kochis? The reader comments can be particularly entertaining.

Disclaimer: Some pages on this site may include an affiliate link. This does not effect our editorial in any way.